This week a friend posited this exercise for a list: our ten favorite works of fiction. I then realized that I had never made such a list before. I scoured my record of everything I’ve read, considered only the perfect-ten A-plusses, and came up with these:

10. Tom Wolfe, A Man in Full

A tour de force of satire, and an absolutely perfect portrait of late 20th century us. A huge achievement in making us look at our warts in the mirror and laugh our heads off at them. By far the best American novel of the 90s.

9. Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomson, The Rule of Four

Incredibly fun puzzle mystery, without being ponderous or pandering. A flawlessly fun read.

8. P.G. Wodehouse, Code of the Woosters

The first Jeeves and Wooster book I ever read, and still the best. We all type LOL every day, it seems, but how often does something actually make us laugh out loud? This book did, many times.

7. James Clavell, Noble House

I didn’t think a 1000 page novel about a British business executive in Hong Kong in the 60s could be the most exciting, engrossing adventure story I’d ever read, but here we are.

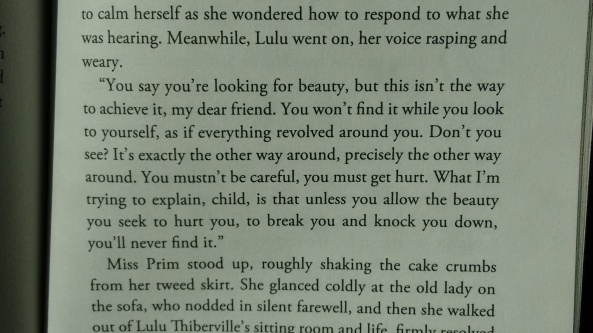

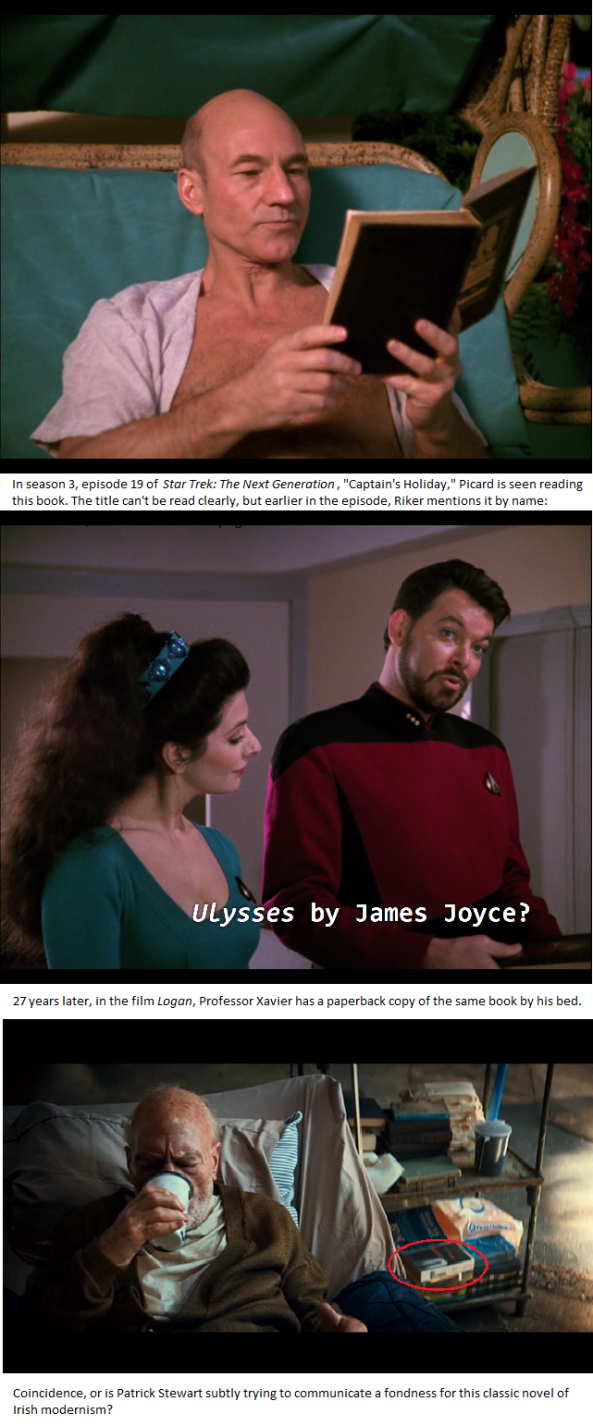

6. James Joyce, Dubliners

A phenomenal achievement of the mind, this little collection of stories has history’s greatest difference between the simplicity of the narratives and the depth of the ideas.

5. Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

The bleak setting, the haunted and violent saga, the elegantly complex plot and style: this is the greatest novel from 19th century England, which is saying a lot.

4. Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove

A surprise, just like Noble House. Who would have thought a long, rambling Western would also be the most humane, exciting, passionate celebration of life I’d ever see between two covers? I wish I could read it again for the first time.

3. Frank Herbert, Dune

The cover of the current paperback edition calls it “science fiction’s supreme masterpiece,” and if anything, that’s playing it safe. This majestic epic broke all the rules, and in doing so, wrote the ones we’ve been following ever since.

2. John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

The one and only truly counter cultural book I’ve ever seen–a story so bogglingly original that it has endless surprises and challenges for everybody…and is genuinely funny on every single page.

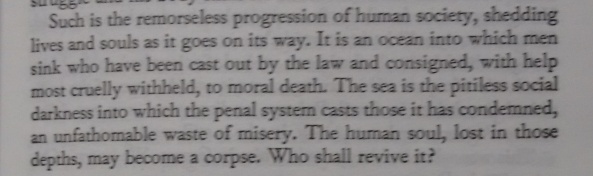

1. Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

It’s difficult to even begin describing the wonders of this super masterpiece. Let just one bit of praise suffice: this grand work has the best rendering of life’s very largest dramas and its very smallest details. One or the other would be enough to put it on this list, but it has both. Amazing.

This is the story of an invisible community, where one voice at a time leads us to connect with others, in a chain back in time.

This is the story of an invisible community, where one voice at a time leads us to connect with others, in a chain back in time.