A pet peeve: people constantly complain–students and adults alike–that they can’t understand Shakespeare because he wrote in “old English.”

No, he didn’t. Shakespeare wrote in exactly the same modern English we still speak and write today. He used a much larger vocabulary, tons of poetic phrasings and figures of speech, a lot of specialized references, and often simply waxed eloquent in his singularly elegant style, but his language was no different from ours.

I realize that when people call it “old English,” they mean precisely the aspects of Shakespeare’s language which I just mentioned, but still, the inaccuracy bugs me. A little effort, time, and homework makes Shakespeare comprehensible and enjoyable, but actual old English is, practically, a foreign language.

Really. Quick English lesson summary: The defining work of modern English is that of one of its earliest practitioners: Shakespeare. Middle English (which could be dated very roughly from about 1000 AD to 1500 AD) is best exemplified by Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Old English is illustrated best by the epic poem Beowulf.

Shakespeare, as I said, can be read with a little effort. In fact, most of us could understand most of his work right now with practically no assistance.

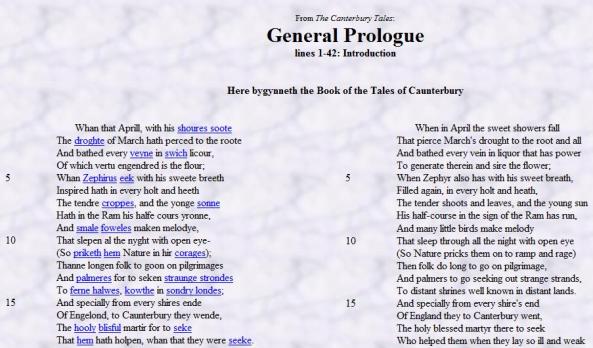

Chaucer, however, is usually “translated” into modern English when printed, as his vocabulary and spelling are so different from what we use today that much of it is very difficult to read. A sample of the middle English text is below, with a modern equivalent to help.

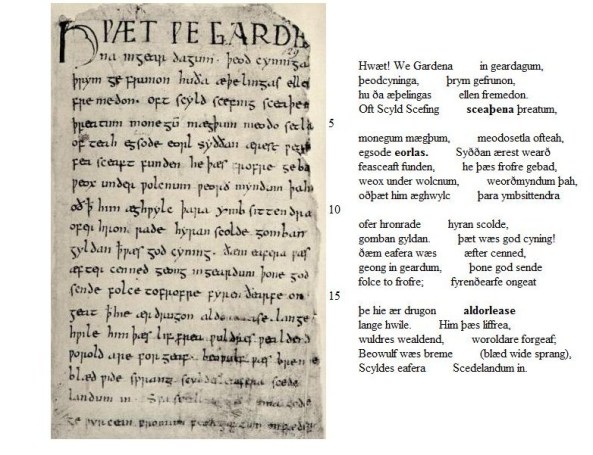

Beowulf, however, originates from the few hundred years before the end of the first millennium, when English was first evolving from German as a distinct tongue. Beowulf shows that old English is basically a foreign language–in some ways, still closer to German than what we consider English today. Not only its vocabulary and spelling, but even its letters are often so different from what we’re used to, that reading much of it at all is almost impossible without training. (I took a history of the English language class in college and learned enough old English to read some of it. It was a lot of fun and I wish I’d brush up on it again.)

A sample of the Beowulf manuscript is below also. Good luck making heads or tails of it.

If nothing else, seeing these bits of old and middle English should help people to realize that Shakespeare is definitely not old English…and really not that bad at all.

The beginning of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, in his own language and adapted for ours. Image courtesy of http://www.librarius.com/canttran/gptrfs.htm.

Here, Here! What really trips people over Shakespeare is his writing in metered verse more than the words anyway.

Your article is correct that scholars usually identify Shakespeare as speaking early modern English, but you are underestimating the number of differences that have accumulated over the last 400 years. The fact that so many people complain about the difficulty of Shakespeare argues against your claim that it only takes a little effort to follow him. It takes a great deal of patience and concentration.

For an interesting article on the difficulty of Shakespeare’s language, see the January 2010 issue of American Theater magazine. John McWhorter, a linguist, makes the case for translating Shakespeare. Here is the link: http://tcg.org/publications/at/jan10/shakespeare.cfm.

If you are interested in what a serious effort at translating Shakespeare looks like, you can see examples of my Shakespeare translations at http://www.fullmeasurepress.com.

Kent Richmond

Kent, Shakespeare is certainly not hard compared to Chaucer and Beowulf, which are much more “old English” than he is, was my point. But, sure, yes, you’re right, too. I like McWhorter’s work (I’ve read a bit of his political stuff at City Journal), and there’s a place for “translating” Shakespeare into contemporary argot, but the fact that many people stuggle doesn’t prove that he’s hard, only that literacy is suffering.

When my kids reached High School, they were glad that we read the scriptures as a family, because they had no difficulty reading and understanding Shakespeare.

Great post! Yes, Old English is much closer to Indo-Germanic, but I can see how teenagers might think the language of Shakespeare sounds old. I agree that with some effort, a modern audience can enjoy Shakespeare. Not that these are super recent examples, but some of Kenneth Branagh’s productions are amazing, particularly Henry V. Although I have read all of Shakespeare’s plays, I personally enjoy it most when I see them performed. It is a tradition for me to take my teenaged daughter and a gaggle of her friends to a free Shakespeare in the Park performance in Henderson. It is something that they all remind me about every year as fall approaches, and is especially enjoyable when it is held at Sonata Park. (Sorry for the shameless plug, but I don’t stand to benefit from it.)

And yet, I can see the flip side of the argument. One could argue that the average vocabulary and reading comprehension levels today make it more challenging for a wide audience to understand and enjoy Shakespeare. Even though there is a vast difference between Shakespeare’s language and that of Old and Middle English, language has changed since the time of Shakespeare. (Notice I didn’t say evolved, as I do not feel many of the changes are for the better). If the (American) English language is viewed through a descriptive lens rather than a prescriptive one, the argument that Kent cited becomes more persuasive. All it takes is to listen to the way people converse around us.

PS, I agree with Floyd the Wonderdog that there are practical as well as spiritual benefits to be gained from reading the scriptures.

Floyd and Mom, you remind me of a profesor I once had who told me he could recognize the religious kids in his classes, though he wasn’t himself, because they were the ones who understood symbolism, poetic grammar, figures of speech, etc. quickly. All that scripture study as kids pays off.

Mom, don’t apologize for the plug…now I want to go!

You’re so right that literacy is suffering. People expect to hear only a few single words and resent having to make a little effort to understand. Any longish sentence brings hoots from the audience (or snores, actually).

English is not even my native tongue, and I have no trouble reading Shakespeare. Sometimes hearing it can be difficult, due to my hearing problems (people pronounce some words so oddly…).

Pingback: 第九十二號:「W」為什麼叫「double U」呢? | 故事